A company, like a person, in addition to taking care of its body (production) should focus on the state of its soul (its ethics) – Alessandra Pellegrini

One of my recent discoveries is the beauty and the power of the Italian language (should have realised it earlier but it is what it is!), which I started to learn after completing my Executive Master studies at SDA Bocconi in Milan. And once I reached the level where I could finally read books, still very very slowly and with the help of a dictionary, it has given my new hobby a completely different flavour.

I don’t remember how exactly but some way I ran into a book by Alessandra Pellegrini, covering the topic, which is very close to my heart and central in my professional development – fundraising and building connections between culture and business. In my recent trip to Italy, I found it at a Feltrinelli store next to the apartment I was staying in Milan and then read it almost in one go during my long return trip home.

The book is based on Alessandra’s personal experience of generating support for the Piccolo Teatro di Milano, La Filarmonica della Scala, Pinacoteca di Brera, FAI (Fondo ambiente italiano / the National Trust for Italy), Museo Diocesano di Milano (The Diocesan Museum of Milan), the environmental restoration of the Last Supper by Leonardo Da Vinci, and many other prominent cultural organisations and initiatives.

Given that “Investire in cultura” is written in Italian, to me, this made it sound even more poetic and engaging. So, I’ve decided to share and translate some of my favorite thoughts and quotes to get you inspired if you’re looking to become a cultural fundraiser or, as Oscar Farinetti, the owner of the high-end Italian food mall chain EATALY, said in a preface, “a fisherman of sensitive souls” / “un pescatore di anime sensibili.” Because, as Alessandra writes in the book, a company, like a person, in addition to taking care of its body (production) should focus on the state of its soul (its ethics and social responsibility).

Alessandra Pellegrini wanted to become a pianist, but during her studies, she decided that she was surrounded by more talented musicians, and her strength was actually in the capacity to understand how to help artists and inspire businesses to support them. Today she sees her mission and the mission of other fundraisers in “creating harmony between culture and companies, between the economy and the beauty.” Similar to piano studies, this path requires “the understanding of the instrument, experimenting with its possibilities, and making it sound the way it should.”

So, who is a fundraiser and what instruments does she (he) need to catch sensitive souls?

What resonated with me is that Alessandra is very clear in defining the role of the fundraiser, because this is “not your ATM” and not “a somebody scrolling through a phone book asking others to pay.” A fundraiser is a member of the team who understands the organisation, its structure, its values, and has the full picture of its budget needs. In this sense, she (he) could be called a foundraiser for its ability to go deep into things and to work on strategy. “No fund without found!”

Among the critical points is the fundraiser’s ability to understand the perception an organisation or a project has in the eyes of others. And if it’s not that visible, then this is something to work on from a strategic point of view.

One of the organisations with which Alessandra collaborated for decades is Fai/ The National Trust of Italy. It was created in 1975 to preserve and to foster appreciation of Italy’s cultural heritage sites, and among its properties there are many castles, villas, monasteries, and house museums around the country.

Concerts at Fai / Fondo per l’Ambiente Italiano properties. Photo by Fai

The events that Fai initially organised were very chic and exclusive, and donations came primarily from the wealthy individuals living next to those heritage sites. Not a great starting point for working with larger publics and generating business support through corporate social responsibility.

This has changed when Fai took a different strategy, decided to engage larger audiences and began holding chamber concerts at its properties where people could come with tickets, thus participating in special experiences and discovering unique places. Such programming changed the perception of the value of the organisation and helped in securing new corporate sponsors.

The book also covers the importance of understanding what actually moves businessmen and entrepreneurs to say ‘yes’ to particular projects.

In case of Pirelli’s partnership with the Orchestra italiana da camera (the Italian Chamber Orchestra), one of the best string orchestras in the world, led by the highly acclaimed Italian violinist Salvatore Accardo, the company decided to support the ensemble and also gave it an auditorium at its new headquarters in Milano Bicocca for new programs preparation. Art and music are the essential parts of Pirelli’s corporate culture, and through this new partnership the company’s employees and their families could enjoy attending concert rehearsals and special performances.

In my research, I also came across another project that the Orchestra italiana da camera did with Pirelli. In 2017, the company commissioned the composer and violist Francesco Fiore to create an original music work, which would become the voice of the new Pirelli Industrial Centre in Settimo Torinese, designed by the world-famous architect Renzo Piano. The piece was specially written for Salvatore Accardo’s violin and performed by the Orchestra italiana da camera. The full story of how the partnership came about and what unites music and factories can be found in Pirelli’s digital project here.

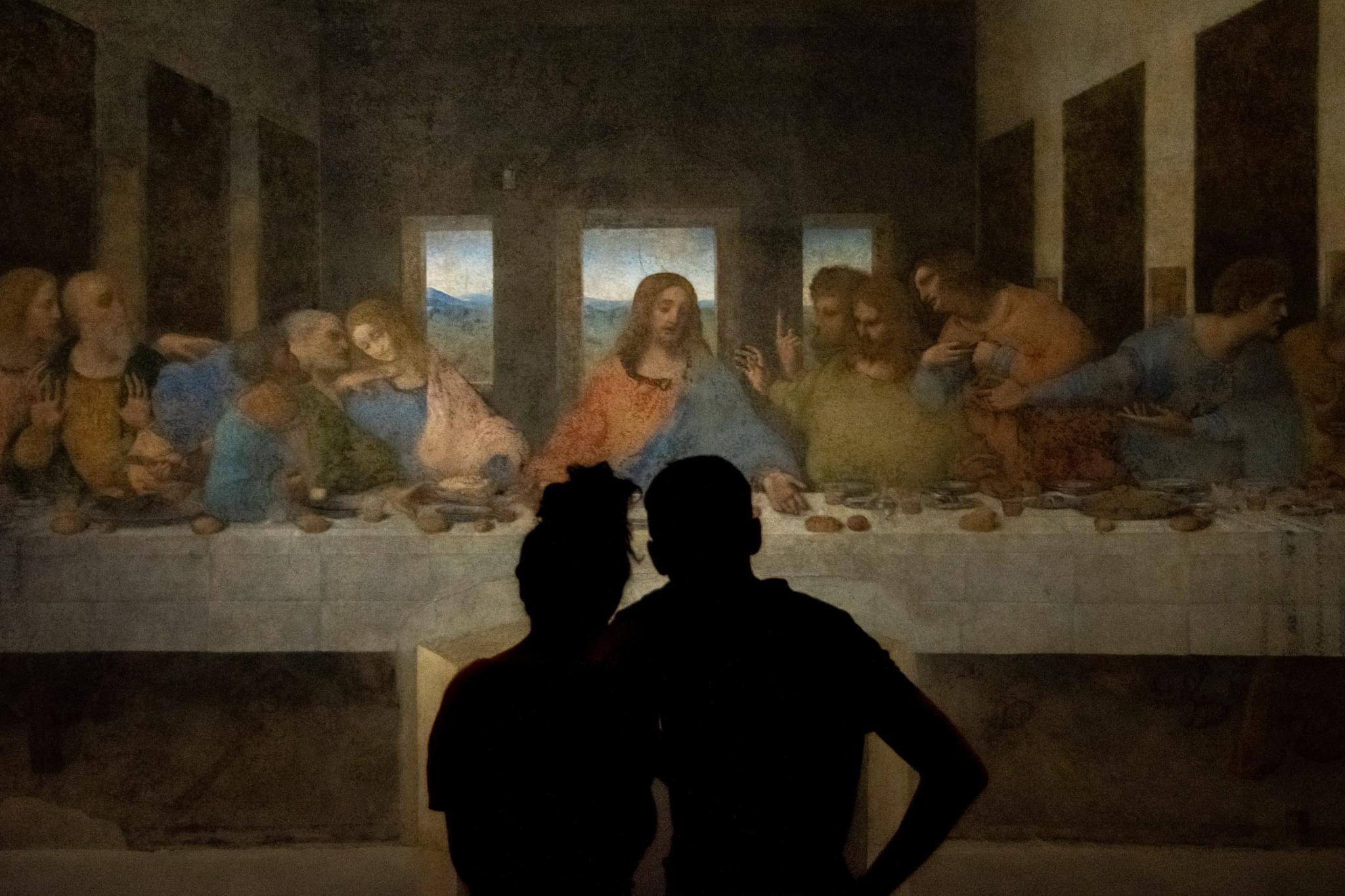

Another interesting example featured in the book is the story of raising funds for the environmental restoration of Leonardo Da Vinci’s Last Supper, which would improve the air purification system in Milan’s Santa Maria delle Grazie church and would help to extend the life of the masterpiece by 500 years. Moved by the idea that the restoration would allow to triple the number of people who could see Da Vinci’s work on a daily basis, EATALY’s Oscar Farinetti agreed to cover the full cost and to become the only private sponsor of the project. He even came up with the slogan for the campaign around the restoration “Una cena cosi non la puoi perdere – Eataly per il Cenacolo” – “The Dinner You Can’t Miss – EATALY for Last Supper.” In 2018, the project was recognised with the Culture + Enterprise Award in the Sponsorships and Cultural Partnerships category.

Last Supper by Leonardo Da Vinci. Photo by Museo del Cenacolo Vinciano

So, to sum up, why culture and why should business support it? Because culture makes us human. Quoting the book, “on the little boat that sails to the new world, if you don’t bring artists on board, you will find yourself in an impoverished world, worse than the one you leave”. And this little boat should also have a space for a fundraiser, who understands all this and believes in the power of art for the future.

Supporting cultural projects is not about immediate sales results. But besides the high level social impact, it makes companies more human and creates a reputational change. It helps to build a community of employees, clients, and partners who can participate in unforgettable cultural experiences. To have a soul, rather than being a strictly production machine. And the role of the fundraiser is to appeal to those souls, and “to connect the earth and the sky” – “tenere insieme la terra con il cielo”.